MASTERS STUDENT URGES COURTS AND LAWMAKERS TO PUT HUMANITY AT THE CENTRE OF JUSTICE

Even the strongest laws fail when they forget the people they were passed to protect.

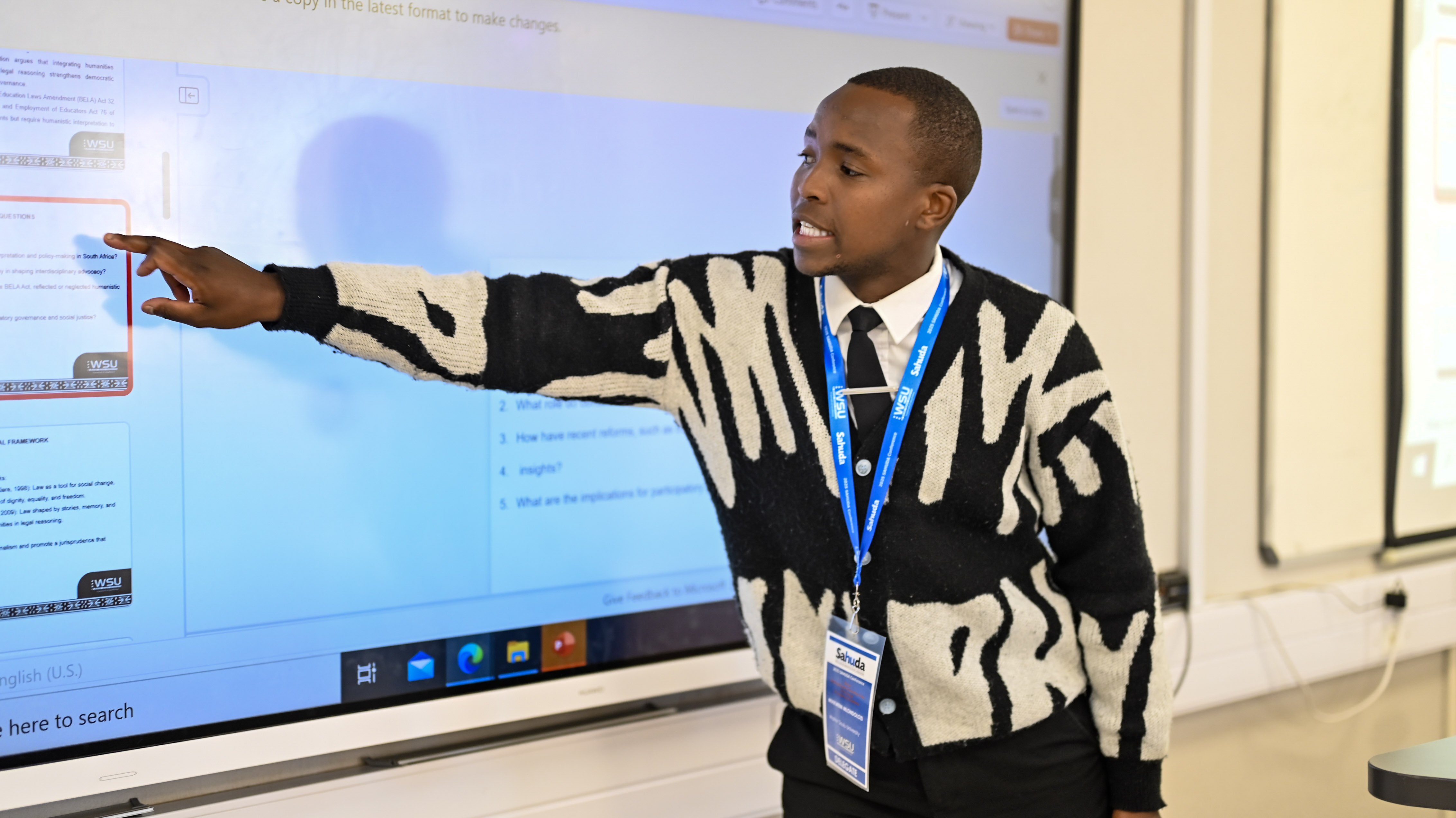

These assertions were made by Walter Sisulu University Masters student, Mlondolozi Mvikweni, at the South African Humanities Deans Association (SAHUDA) Conference held at WSU on 23 October.

Legislative acts such as the Basic Education Laws Amendment (BELA) Act and the National Health Insurance (NHI) Act, he noted, exemplified policies that exist within the legal framework yet struggle to take effect in people’s everyday lives.

“If we talk about the NHI and the BELA acts, in terms of Transformative Constitutionalism, they are not applied. They are laws passed for citizens, but they are not currently serving the purpose they are made for. This means that we assume that the law is not practical in nature, but it is only in codification,” expressed Mvikweni.

Presenting a study titled Integrating Law and Humanities to Strengthen Policy-Making And Advocacy Through Constitutional Values, Mvikweni highlighted the persistent gap between South Africa’s legal framework and the lived realities of ordinary citizens.

Using cases of rape to illustrate his point, Mvikweni said the gap between law and life was visible in how such cases were handled in practice.

“For example, in rape cases, the trial process tends to focus on the perpetrator, leaving the survivor on the sidelines. The victim is only brought in to testify and then dismissed, yet it is their suffering that should guide the interpretation of justice,” he noted.

Mvikweni asserted that such an approach exposed the risks of treating the law as a purely technical system, detached from moral and emotional context.

He continued to argue that South Africa’s legal framework, though progressive on paper, often failed to reflect the lived realities of the people it aimed to protect.

Mvikweni also referenced landmark constitutional cases such as the Minister of Health v Treatment Action Campaign and the Economic Freedom Fighters v Speaker of the National Assembly, as examples of how the courts have, at times, engaged implicitly with humanistic values.

These cases, he said, demonstrated that when legal interpretation is guided by empathy, and ethical responsibility, it produced outcomes that aligned more closely with the democratic and social justice values enshrined in the Constitution.

“The humanistic approach of the law changes the outcomes because it is drawn from the lived experiences of the people,” he said.

Mvikweni urged law schools to bridge the gap between theory and practice by encouraging students to engage directly with communities, test the applicability of existing policies, and understand the ethical implications of every legal decision.

Ultimately, Mvikweni’s research invited lawmakers, and educators to reimagine justice not as a cold procedure, but as a living, humane practice grounded in compassion and experience.

The conference ends Friday, 24 October.

By Yanga Ziwele